Gastrointestinal Medication Absorption Calculator

Medication Information

Gut Factors

Estimated Absorption Impact

This medication may experience 0% reduction in effectiveness due to these factors.

Take a pill. Swallow it. Wait for it to work. Sounds simple, right? But for millions of people, that everyday act doesn’t guarantee the medicine will even reach their bloodstream-let alone work the way it’s supposed to. Gastrointestinal medications face a gauntlet of biological barriers before they can do their job. And if any part of that journey goes wrong, the drug might as well be water.

Here’s the hard truth: up to 80% of all medications are taken by mouth. That’s because pills are easy, cheap, and non-invasive. But the human gut isn’t designed to be a drug delivery system. It’s designed to break down food, kill pathogens, and absorb nutrients. And it does that job too well-often stopping medicines in their tracks.

Why Your Stomach Is the Enemy of Some Drugs

The stomach is acidic-pH 1.5 to 3.5. That’s strong enough to dissolve metal. Many drugs can’t survive that environment. Take penicillin or insulin: they’d get shredded before they even left the stomach. That’s why some medications come in enteric coatings-special shells that only dissolve in the less acidic small intestine. If that coating breaks too early, the drug fails. If it breaks too late, the drug doesn’t get absorbed in time.

But even if the pill survives the stomach, the real battle begins in the small intestine. This is where most drugs are absorbed. The surface area here is massive-about the size of a tennis court. But that doesn’t mean absorption is guaranteed. The intestinal wall is lined with a thick mucus layer, tight junctions that seal cells together, and proteins like P-glycoprotein that actively pump drugs back out. Think of it like a bouncer at a club: if your drug looks suspicious, it doesn’t get in.

Food Isn’t Just a Meal-It’s a Drug Saboteur

Doctors tell you to take some meds on an empty stomach. They’re not being picky. They’re saving your life. Fatty meals can delay gastric emptying by 2 to 4 hours. That means a drug like levothyroxine, which needs to be absorbed quickly and consistently, sits in your stomach while your body digests bacon and eggs. Result? Blood levels drop by 30-50%. That’s not a small difference. For thyroid patients, it can mean fatigue, weight gain, or worse.

Even caffeine and grapefruit juice can interfere. Grapefruit blocks enzymes that break down certain drugs, causing dangerous buildup. Coffee speeds up gut movement, which can flush out slow-absorbing meds before they’re fully taken up. And don’t forget fiber. High-fiber diets can bind to drugs like digoxin or statins, pulling them out of circulation before they do their job.

What Happens When Your Gut Is Sick

People with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or short bowel syndrome don’t just have inflamed guts-they have broken drug delivery systems. In ulcerative colitis, the lining of the colon is damaged. That’s where delayed-release mesalamine is supposed to dissolve. But if the inflammation is too severe, the drug gets released too early, washed away before it can act. Studies show these patients absorb 25-40% less of the drug than healthy people.

Short bowel syndrome is even worse. If you’ve lost half your small intestine, you’ve lost most of your absorption surface. Patients often need two or three times the normal dose of antibiotics, vitamins, or pain meds just to get the same effect. And even then, it’s unpredictable. One patient on a Crohn’s forum said their Remicade levels swung from undetectable to therapeutic-without changing their dose. That’s not noncompliance. That’s physiology gone rogue.

And then there’s GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide. These weight-loss and diabetes drugs slow down gut motility. That’s good for blood sugar control. Bad for everything else you take. A study found they reduce absorption of other oral meds by 15-30%. That’s huge for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin. Pharmacists report INR levels in IBD patients on warfarin swinging from 1.5 to 4.5 without any dose change. One point out of range can mean a stroke or a bleed.

Formulation Matters More Than You Think

A pill isn’t just a pill. It’s a carefully engineered system. The same active ingredient can behave completely differently depending on whether it’s a tablet, capsule, suspension, or chewable. Salt forms, crystal structures, and particle size all affect how fast the drug dissolves. If dissolution is slower than absorption, you’re stuck. That’s why some drugs are formulated as nanoparticles or liposomes-they sneak through the gut lining like undercover agents.

There are also absorption enhancers. Sodium caprate, chitosan, and medium-chain fatty acids can temporarily open tight junctions between cells, letting drugs slip through. These aren’t magic. They’re used in specific formulations for drugs that otherwise wouldn’t work. For example, some insulin patches use these to get the molecule across the gut wall. In clinical trials, they’ve boosted bioavailability by up to 200%.

But here’s the catch: these enhancers aren’t in most over-the-counter meds. They’re in specialized, often expensive, formulations. Only 15-20% of oral drugs on the market have labeling that even mentions use in GI disease patients. Most doctors don’t know the options exist.

Why Two People Can Take the Same Pill and Get Different Results

Two people with the same diagnosis-say, Crohn’s-can take the exact same dose of the same drug and have wildly different outcomes. Why? Because their guts aren’t the same. Transit time varies. pH levels shift. Mucus thickness changes. Blood flow to the intestine fluctuates. Even their microbiome can alter drug metabolism.

Dr. Caitriona O’Driscoll from Trinity College Dublin says it plainly: you can’t predict malabsorption just by knowing the drug’s chemistry or the disease. There’s too much variability. That’s why some patients respond to a drug one month and not the next. It’s not they’re lying. It’s not they’re inconsistent. It’s their gut changed.

This is why pharmacists who specialize in GI care need 6 to 12 months of training just to understand the variables. Most general practitioners don’t have that depth. And drug labels? Most don’t even mention GI disease risks. The FDA’s own guidelines admit this gap.

What You Can Do About It

If you’re taking oral meds and they’re not working, don’t assume it’s your fault. Ask these questions:

- Is this medication supposed to be taken on an empty stomach? If yes, are you eating within 2 hours before or after?

- Are you taking it with grapefruit juice, coffee, or high-fiber foods?

- Do you have a GI condition? If yes, has your doctor adjusted your dose or formulation?

- Are you on a drug like semaglutide? If so, are other meds you take affected by slowed digestion?

- Is there a liquid, chewable, or extended-release version available? Sometimes switching formulations makes all the difference.

Keep a log. Note when you take your meds, what you ate, and how you felt. Bring it to your pharmacist. They’re trained to spot absorption issues. A simple switch-from tablet to suspension, or from immediate to delayed release-can turn a failed treatment into a successful one.

The Future Is Personalized Delivery

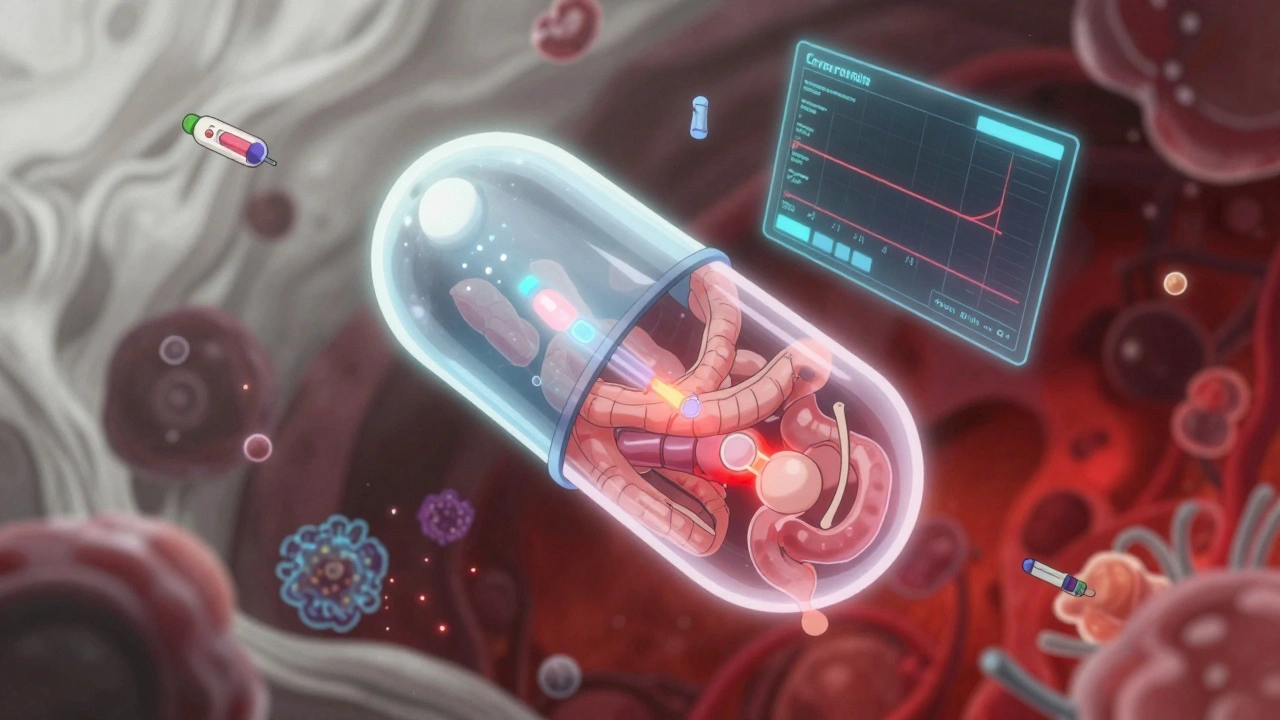

Scientists are building smart capsules that measure pH, pressure, and transit time inside your gut. These sensors send data to your phone, helping doctors tailor dosing in real time. Early trials are showing promise. One study (NCT04567890) used this tech to adjust doses of antibiotics in Crohn’s patients-cutting treatment failures by nearly half.

And with 70% of new drugs in development weighing more than 500 Daltons, the problem is only getting worse. Big molecules like biologics don’t absorb well orally. That’s why most are injected. But if we can crack oral delivery for these drugs, we could replace needles with pills for diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, even cancer treatments.

The global market for absorption enhancers is expected to hit $2.8 billion by 2027. That’s not just business-it’s hope. For the millions of people whose meds don’t work because their gut won’t let them, the next breakthrough might not be a new drug. It might be a better way to get the old one into their blood.

Been on levothyroxine for 8 years and this is the first time someone explained why my levels keep dropping when I eat avocado toast for breakfast. No wonder I felt like a zombie every winter.

Switched to taking it at bedtime with a big glass of water and boom - stable TSH. Why don’t more doctors just tell you this?

Let’s be real - the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know how unreliable oral meds are. Why? Because if people realized 80% of pills are basically lottery tickets, they’d demand better delivery systems. Instead, we get more pills. More side effects. More blame on patients for ‘noncompliance.’

It’s not your fault. It’s systemic failure wrapped in a pill bottle.

And yes, I’ve had my Remicade levels swing from zero to therapeutic without changing anything. My GI doc called it ‘biological chaos.’ I call it being a guinea pig.

Ugh here we go again with the ‘gut is broken’ nonsense. You people take your meds wrong, then blame the science. I’ve been on 3 different antibiotics for Crohn’s and never had an issue. You just don’t follow instructions. Stop making excuses. Take your damn pill on an empty stomach like the label says. It’s not rocket science.

Also, grapefruit juice is for amateurs. Real men drink coffee and take their meds like adults.

India has been solving this for decades - we’ve got Ayurvedic formulations that bypass gut absorption entirely! Why are we still using Western pills that get destroyed by stomach acid? We’ve got herbal nanocarriers that deliver curcumin directly to the colon - no coating needed!

And yet, Americans pay $500 for a pill that dissolves in 20 minutes while we use turmeric paste with black pepper and get better results? The West is obsessed with chemistry, not biology!

Also, why are you drinking coffee? Drink ginger tea. It’s natural. It’s ancient. It’s Indian.

This article is dangerously misleading. It implies that pharmaceutical companies are negligent, when in fact, they are constrained by regulatory bodies that refuse to approve novel delivery systems due to ‘unproven long-term safety.’

Furthermore, the suggestion that patients should ‘switch formulations’ without consulting a physician is reckless. This is not a DIY medical forum. The author has no medical license and is promoting self-diagnosis under the guise of education.

And for the record - grapefruit juice is not a ‘saboteur.’ It’s a CYP3A4 inhibitor. Learn the terminology before you write.

gut is a gatekeeper

drugs are intruders

we’re just guests in our own bodies

maybe we’re asking the wrong questions

not ‘why won’t this work’

but ‘why are we forcing medicine into a system that wasn’t built for it’

maybe the real fix isn’t better pills

but better respect for biology

we treat our guts like a vending machine

but it’s a cathedral

and we’re just throwing coins in the dark

OMG I CRIED reading this 😭 I’ve been on semaglutide for 6 months and my blood pressure meds kept failing - I thought I was dying or going crazy… then I read about the 30% absorption drop and it all made sense. My pharmacist finally listened after I showed her this article. We switched me to a patch. I feel like a new person. Thank you for not blaming us. 🙏❤️

Did you know the FDA doesn’t require drug manufacturers to test their pills on people with IBD? None of the clinical trials include Crohn’s patients. So every time you take a pill, you’re basically participating in an unregulated experiment.

And the ‘absorption enhancers’? They’re mostly patented by Big Pharma and priced at $2000/month. You think they want you to know you can get 200% better bioavailability for $50? Nah.

They’d rather you keep buying the same pill and blaming yourself when it doesn’t work.

Wake up.

It’s not your gut.

It’s the system.

As a Nigerian pharmacist who worked in Lagos for 12 years, I can tell you - this problem is global. In rural areas, people take antibiotics with palm oil, yam porridge, or bitter leaf juice. Sometimes it works. Sometimes they die. We had a child with malaria who didn’t respond to artemisinin - turned out her mother mixed it with local herbal tea that bound the drug. We had to switch to injection. No one told her about interactions.

Education is the real gap. Not formulation.

And yes - fiber does bind drugs. We’ve seen it with antiretrovirals too.

This isn’t just a Western problem. It’s a human problem.

I just want to say - if you’re reading this and you’ve ever felt like you’re failing because your meds don’t work, please know you’re not alone. I have Crohn’s and took my levothyroxine for years thinking I was lazy or not trying hard enough. I cried when I found out my gut was just absorbing 40% of it. I didn’t know it was possible to have a ‘broken delivery system.’

It’s not your fault. It’s not your body being weak. It’s biology being complicated.

And you deserve better. You deserve a doctor who listens. You deserve a pharmacist who asks about your meals. You deserve a pill that actually works.

I’m so proud of you for being here. Keep asking questions. Keep advocating. You’re not weird. You’re just smart enough to notice something’s off - and that’s a gift.

And if you need someone to talk to - I’m here. Always.

Why are you taking pills at all? Why not use Ayurveda or traditional Chinese medicine? They’ve been doing this for 5000 years without these fancy coatings and nanoparticles. You’re just addicted to Western medicine because it’s branded and expensive. Your gut is fine - your mindset is broken. Stop blaming the pill. Blame your dependency on corporate drugs.

Everyone here is acting like this is new information. I’ve been telling my patients for years that fiber binds statins. I’ve had people on 80mg atorvastatin with LDL of 190 because they eat bran cereal at breakfast. I tell them to take it at night. They say ‘but I read online it’s better in the morning.’

Then they wonder why their doctor thinks they’re noncompliant.

It’s not the drug. It’s the ignorance.

And now you’re all acting like this is some revolutionary revelation? Please.

My 72-year-old patient knew this in 2008.

It is imperative to underscore the profound epistemological lacuna within contemporary pharmacological discourse, wherein the ontological primacy of the gastrointestinal milieu is systematically subordinated to the hegemony of pharmacokinetic reductionism. The conflation of bioavailability with therapeutic efficacy constitutes a categorical error, predicated upon an impoverished phenomenological model of the human organism as a mere conduit for molecular transference, rather than a dynamic, co-evolved ecosystem wherein drug absorption is but one emergent property among countless entangled physiological variables.

Furthermore, the normalization of patient self-reporting as a diagnostic heuristic - as suggested in the concluding section - constitutes a dangerous epistemic capitulation to lay epistemologies, undermining the epistemic authority of clinical pharmacology.

One must ask: if the gut is so unpredictable, why do we continue to rely on oral administration at all? The answer, regrettably, lies not in science, but in the commodification of convenience.