Ever filled a prescription for a generic drug and been shocked by the price - only to find out the same pill costs $4 if you pay cash? You’re not alone. In the U.S., the system that sets prices for generic medications is broken, opaque, and stacked against patients. It’s not about the cost of making the drug. It’s about who controls the negotiations between insurers, pharmacies, and middlemen called Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). And what you pay at the counter? That’s often just the tip of a very complex iceberg.

Who Really Sets the Price of Your Generic Pills?

The real power behind generic drug pricing doesn’t live at your local pharmacy or even in your insurer’s office. It’s held by a handful of giant middlemen: OptumRx, CVS Caremark, and Express Scripts. Together, these three PBMs control about 80% of the market. They don’t make drugs. They don’t dispense them. But they decide how much pharmacies get paid - and how much you pay - for every generic pill covered by your insurance.

Here’s how it works: PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers for bulk discounts. They then create a list called the Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) - the highest amount they’ll reimburse a pharmacy for a generic drug. That number is rarely public. It’s buried in contracts. And it’s often way higher than what the pharmacy actually paid for the drug.

The Hidden Profit: Spread Pricing

One of the most confusing - and damaging - practices is called spread pricing. It’s simple: the PBM charges your insurance plan $45 for a generic blood pressure pill. But the pharmacy only gets $12 back. The $33 difference? That’s the PBM’s profit. And you never see it. You’re just told, “Your copay is $45.”

Worse, that $45 isn’t even the real cost of the drug. The pharmacy might have bought that same pill for $4 from a wholesaler. But because of the way PBMs structure contracts, pharmacists can’t tell you that. A 2024 report found 92% of PBM contracts include “gag clauses” that legally prevent pharmacists from telling patients they could pay less out of pocket.

That’s not a glitch. It’s the business model. According to Evaluate Pharma, PBMs made $15.2 billion in 2024 from spread pricing - and 68% of that came from generic drugs. The more you pay through insurance, the more they make. Your copay isn’t a cost-sharing tool. It’s a revenue generator.

Why Your Copay Is Higher Than Cash

It sounds impossible - but it’s happening every day. A 2024 Consumer Reports survey found 42% of insured adults paid more for a generic drug with insurance than they would have if they’d paid cash. One Reddit user shared: “I paid $45 for my generic metformin with insurance. Walked into another pharmacy, paid $4.50 cash. No insurance needed.”

This isn’t rare. It’s systemic. Why? Because PBMs set reimbursement rates based on outdated benchmarks like Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is often inflated by drugmakers. Pharmacies get paid based on that fake number. But cash-paying customers pay the real market price - the actual cost the pharmacy paid. That’s why GoodRx and Cost Plus Health can offer prices lower than your insurance copay. They bypass the PBM system entirely.

The Real Cost to Pharmacies

Independent pharmacies are getting crushed. They’re forced to accept reimbursement rates set by PBMs - rates that sometimes don’t even cover the cost of the drug, let alone the staff, rent, and software to process claims. A 2024 report from the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 11,300 independent pharmacies closed between 2018 and 2023.

Why? Because of clawbacks. A PBM pays a pharmacy $12 for a drug. Later, they review the claim, decide the drug was worth less, and demand $3 back. That’s right - they take money after the fact. A 2023 FTC report found 63% of independent pharmacies have been hit by clawbacks. Many now spend hundreds of hours a year just decoding PBM contracts. Some hire PBM specialists for $100,000 a year just to keep from going under.

Who Benefits? Not Patients

The system claims to save money. But the numbers don’t add up. In 2024, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. That means the bulk of the $620 billion prescription drug market is driven by brand-name drugs - and the PBM system doesn’t fix that. Instead, it shifts costs around.

Drugmakers inflate list prices to offer bigger rebates to PBMs. The higher the list price, the bigger the rebate. That’s why a drug might have a $100 list price, but the PBM gets $80 back. The insurer pays less. The PBM pockets the rest. And you? You pay a copay based on that inflated $100 price - even if you never see any of the rebate.

Dr. Joseph Dieleman of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation put it bluntly: “The current PBM system creates perverse incentives where higher list prices generate larger rebates, ultimately increasing patient cost-sharing burdens.”

What’s Changing? And When?

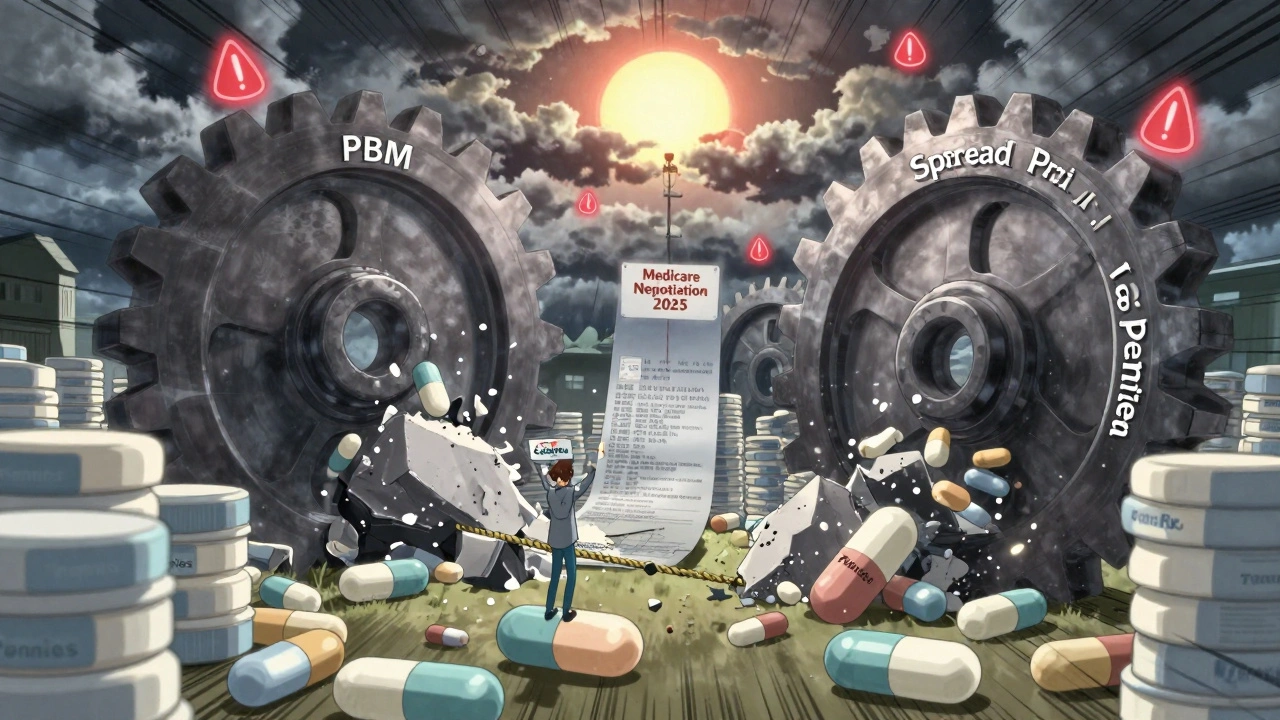

Pressure is building. In September 2024, the Biden administration ordered PBMs to stop spread pricing in federal programs by January 2026. That’s a start - but it only affects Medicare, Medicaid, and VA prescriptions. Private insurance? Still wide open.

Forty-two states are now passing laws to force PBM transparency. Some require PBMs to disclose MAC lists. Others ban gag clauses. The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025, currently in Congress, would require PBMs to pass 100% of rebates to insurers - meaning savings could actually reach patients.

The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, launched under the Inflation Reduction Act, is also starting to influence the market. By negotiating prices directly with drugmakers for 20 high-cost drugs in 2025, CMS is showing that direct negotiation works. Stanford researchers estimate that if this model expanded to commercial insurance, it could save $200-250 billion over ten years.

What Can You Do Right Now?

You don’t have to wait for Congress to fix this. Here’s what works:

- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?” Even if you have insurance, paying cash is often cheaper - especially for generics.

- Use apps like GoodRx, SingleCare, or Cost Plus Health. They show real-time cash prices and often beat your insurance copay.

- Ask your insurer for a list of preferred generics. Not all generics are treated the same. Some have lower copays.

- If your copay is way higher than expected, file a complaint with your state’s insurance commissioner. Consumer pressure is starting to move the needle.

- Consider switching to a health plan that doesn’t use a big PBM. Some small insurers and employer plans offer transparent pricing - they’re rare, but they exist.

The truth? Generic drugs aren’t expensive. The system is. The pills themselves cost pennies. The real cost is in the layers of middlemen, hidden fees, and broken incentives. Until the structure changes, the best protection you have is knowing your rights - and knowing how to shop.

Why is my generic drug more expensive with insurance than without?

Because your insurance plan uses a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) that charges your plan more for the drug than it pays the pharmacy. The difference - called spread pricing - is kept as profit by the PBM. Meanwhile, cash-paying customers pay the pharmacy’s actual cost, which is often far lower. You’re paying for the PBM’s hidden fee, not the drug.

What is a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list?

A MAC list is a secret pricing schedule created by PBMs that sets the highest amount they’ll reimburse a pharmacy for a generic drug. It’s based on outdated benchmarks like Average Wholesale Price (AWP), not real market prices. Pharmacies are paid based on this number - even if they bought the drug for much less. This allows PBMs to profit from the gap.

Can my pharmacist tell me the cash price?

Legally, many can’t - because 92% of PBM contracts include “gag clauses” that forbid pharmacists from informing patients about lower cash prices. But those clauses are being challenged in court and banned in many states. Always ask anyway. Many pharmacists will still tell you, especially if you’re persistent.

Are generic drugs really cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Yes - but only if you pay the real price. Generics are chemically identical to brand-name drugs and cost 80-85% less to make. But because of how PBMs set reimbursement rates, your insurance copay might not reflect that savings. Paying cash or using discount apps like GoodRx often gives you the true low price.

What’s being done to fix this system?

Federal rules banning spread pricing in Medicare and Medicaid take effect in January 2026. Forty-two states are passing transparency laws. Congress is considering bills to force PBMs to pass rebates to insurers. And the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program is proving direct negotiation works. But change is slow - and until PBMs are forced to operate in the open, patients will keep paying more than they should.

Man, this whole PBM mess is wild when you think about it. I used to work in pharma logistics in Bangalore, and I saw how these MAC lists were just made up out of thin air-some guy in a cubicle in Minnesota picks a number based on a 2018 spreadsheet and suddenly it’s gospel. And the clawbacks? I had a cousin who ran a small pharmacy in Chennai, and they got hit with a $200 clawback on a $4 pill because the PBM ‘re-evaluated’ the AWP. He cried. Not joking. He had to sell his scooter to cover it. The system isn’t broken-it’s designed this way to extract every penny possible from people who just need their meds to live. And the worst part? No one in the chain actually gives a damn.

So let me get this straight-you’re saying paying cash is better? Wow. Groundbreaking. Next you’ll tell me breathing air is healthier than breathing smoke. Of course the cash price is cheaper. The pharmacy bought it for $4. But you’re ignoring the fact that insurance pools risk and spreads cost across millions. Your ‘cash is king’ logic only works if you’re rich enough to pay $400 upfront for insulin every month. Most people can’t. So stop pretending this is about fairness-it’s about privilege.

OMG this is so obvious yet no one talks about it?? Like how are people still surprised?? PBM’s are just corporate vultures with fancy titles!! They don’t make anything!! They don’t deliver anything!! They just sit there like spiders in a web sucking money from EVERYONE!! And pharmacists? They’re slaves!! GAG CLAUSES?? That’s illegal in my country!! How is this even legal in the US?? Someone should sue them into oblivion!!

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been a pharmacist for 17 years and this is my daily reality. I’ve had patients cry because they had to choose between insulin and groceries. I’ve had to lie to them because the contract says I can’t tell them the cash price. But I do anyway-quietly, under my breath, with a wink and a ‘check GoodRx.’ I’ve saved so many people money just by whispering ‘try this app.’ And yeah, I’m tired. But I’m not giving up. If you’re reading this and you’re on meds-always ask. Always check. You’re not being annoying-you’re fighting back. 💪❤️

Ohhhhh... so THIS is why I feel like I’m being gaslit every time I go to the pharmacy?? It’s not my fault I’m poor-it’s the SYSTEM!! The PBM’s are the new feudal lords!! They don’t ride horses-they ride algorithms!! And we’re the serfs, paying for the privilege of breathing!! And the worst part? We’re all complicit!! We keep using insurance because we’re told it’s ‘better’-but it’s just a rigged casino where the house always wins!! I feel like I’ve been living in a dystopian novel written by a Wall Street intern with a vendetta!!

Wow. So the whole thing’s a scam. Cool. I guess I’ll just stop taking my meds then. Not like I care enough to fight it. I’ve got Netflix to binge and a cat to pet. This is why I don’t trust ‘systemic change.’ Too much effort. Just tell me where to get the cheapest pills and I’ll be on my way.

This is the most emotionally manipulative piece of journalism I’ve read in months. You’re weaponizing the suffering of patients to sell outrage. Do you even realize how many people rely on these PBMs to access affordable care? You’re painting a picture of villains when the truth is far more complex. The system is flawed, yes-but demonizing middlemen won’t fix it. It’ll just make patients more confused. And honestly? You’re not helping. You’re just making people feel worse.

I’m a single mom in Ohio and I just paid $52 for my son’s generic Adderall with insurance. Walked to the next CVS and paid $4.75 cash. I cried in the parking lot. Not because I was mad-I was just… shocked. Like, how is this possible? I’ve been told my whole life that insurance is there to help. But it’s like they’re charging me for the privilege of being sick. I don’t know how to fix it, but I’m telling everyone I know. Please, if you’re reading this-ask for the cash price. Even if you think you can’t afford it. You can. And you deserve to know the truth.

Hey everyone-just wanted to say this thread is actually really important. I work for a small nonprofit that helps low-income families navigate prescriptions, and we’ve seen this exact thing play out every single week. The good news? More people are learning. More pharmacists are breaking gag clauses. And apps like GoodRx are becoming lifelines. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, start small: ask one question at the pharmacy. Share one tip with a friend. Change doesn’t come from one law-it comes from millions of people waking up and refusing to be silent. You’re not alone in this. We’re in it together.

Per the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ 2024 PBM Accountability Report (DHHS-2024-PBM-01), spread pricing accounted for 68% of PBM revenue derived from generic medications, with OptumRx alone generating $5.1B in non-transparent spread income. Furthermore, FTC data indicates that 63% of independent pharmacies experienced clawback events exceeding $100 monthly, with 41% reporting net losses on generic dispensing. The MAC list opacity constitutes a violation of the 2020 Transparency in Coverage Rule (45 CFR 147.210), yet enforcement remains inconsistent. Structural reform is not merely advisable-it is legally imperative.

i just wanted to say… thank you. i’ve been too scared to say anything because i thought i was the only one. i pay $40 for my thyroid med with insurance. cash is $3. i didn’t know it was legal to tell me that. i felt so stupid. but now i do. and i’m telling my mom. and my sister. and my neighbor. it’s not much… but it’s something. thank you for not making me feel crazy.

Just an FYI-this isn’t just a U.S. problem. In Canada, we don’t have PBMs, and generic prices are regulated nationally. You pay $4 or less for most. No magic. No spreads. No gag clauses. It’s just… simple. The U.S. doesn’t have to be this way. We’ve proven it’s possible. It’s a political choice. Not an economic one.

Why aren’t you blaming the drug manufacturers?? They’re the ones inflating the AWP!! And why are you letting PBMs take all the blame?? They’re just doing their job!! The real villains are the greedy corporations that make the drugs!! And the FDA!! And Congress!! And the pharmacies!! And the patients who don’t shop around!! Everyone’s guilty!!